What it feels like to run a lap at Hayward Field

The Prefontaine Classic served as crash course for a reporter who's long kept track and field at an arm's length.

EUGENE — For a guy whose newsletter is based upon the premise of being somewhat educated on the comings and goings of sports in this state, track and field has been a blind spot.

Ashton Eaton? Never saw him. Same goes for Deajah Stevens, football star Devon Allen or any of the other names made famous at one of the sport’s most hallowed venues. At The Oregonian, we had Ken Goe. At The Athletic, I focused on football. So, admittedly, it was an odd fit to snag a credential for the weekend’s Prefontaine Classic, then accept an invitation to run in the Saturday morning media-only 400 meter race at Hayward Field.

Friday night was my first night covering anything at Hayward in nearly a decade — and with an 8:15 race time the next morning, I cut back for the hotel around 10 p.m. with a couple of events remaining. Halfway between Hayward and bed, a peer through the glass of the Wild Duck Cafe on Villard St. revealed a bar that appeared to be beyond last call. In the distance, the faint sound of the crowd cheering the final laps of the men’s 5,000 meters echoed throughout the Oregon campus.

“Still open,” a bartender said, cracking the door.

The Wild Duck is a game day stop. It’s at its busiest after Matthew Knight Arena empties across the street, serving as a gathering place for fans and players of the sport in season. Now, with the calendar turned to May, Eugene has morphed into Track Town.

After the 2020 season ended with a pandemic and the 2021 season’s schedule rearranged with the Olympic trials, there’s not much of a book on what to expect yet for the new Hayward Field. The city is expecting an influx of 30,000 people for July’s World Championships, a 10-day event that projects as an economic boon for places like the Wild Duck. But on this Friday night, the rhythm of new Hayward is still a bit of a mystery.

Wondering if he could expect much more of a crowd, the bartender asked if there were many still left in the stadium. They had announced 4,812. There might yet be a few stragglers.

“We’re still getting used to this thing,” he said.

The first night of the meet had wrapped up by the time he returned with an IPA and Pilsner, and with a crowd beginning to come through the Wild Duck’s doors he dropped the beers off at the table and took his position behind the bar.

He’d be too busy to return again.

My company was no stranger to Hayward. Andrew Greif, my former football beat partner, was a state champion long jumper at North Bend and competed for a few seasons with the Ducks at old Hayward. He was in attendance in 2001 when 18-year-old Alan Webb shattered the national high school record with a 3:53.43 run in the Bowerman Mile. Greif came to Eugene 21 years later, in part, to see if California high schooler Colin Sahlman could harness some of the same magic.

“I was an eighth grader watching [Webb’s run],” Greif said. “I told Colin this week when I saw him that it was kind of freaky to be talking to him about a record that I saw happening in front of me.”

In a 14-man field in damp conditions, Sahlman finished in 3:56.24, good for the third-fastest time in high school history.

“I’m still proud of it,” Sahlman would tell Greif on Saturday. “I was hoping for a little better, but I still got to race in the Diamond League against the best in the world, so it was amazing.”

With a wider focus than Greif, I spent my Friday night at the track trying to figure out how to watch a meet. The cadence is different in a track stadium than any other venue. One second you hear the crowd cheering the leaders passing by in the women’s 10,000 meters, then in another corner of the stadium applause erupts in front of the high jump pit and, hey, is that the women’s discus going on down on the field?

After American record holder Valarie Allman won the discus and praised Hayward as a wonderful soon-to-be home host for the world championships, Francine Niyonsaba put on a show by becoming the second woman in history to run two miles under 9 minutes. From Burundi, Niyonsaba’s 8:59.09 effort put her so far ahead of the pack that the tension of the race came thanks to the field’s new “Wavelight” pace setting system. It was thrilling watching the 2016 Olympic silver medalist chase a series of purple LED lights set to the pace of the world record.

“I didn’t even see them too much,” Niyonsaba said. “I was focusing on the laps.”

I believe her. I don’t remember seeing the lights during my race, either.

I felt surprisingly spry entering Hayward Saturday morning considering the earlier anecdote about the bar, and the chocolate chip muffin top I had for breakfast. While the media 400 was described as a “FUN” event in the invitation, a series of nerves and chills set in while warming up on the same track Steve Prefontaine once ran around.

Sure, the stadium has changed. Prefontaine’s likeness now oversees the $270 million facility from the Northeast tower, but it’s the same footprint. It’s still the same ground.

I don’t remember much about what happened from the time I made my last stop in the bathroom to when I took lane No. 7 to when the gun went off to when my legs began to wobble with 100 meters to go. What I do remember was the sound coming around Bowerman Curve — a mixture of applause, my heart beating out of my chest and a voice over the PA system promising the crowd free biscuits and gravy if I finished.

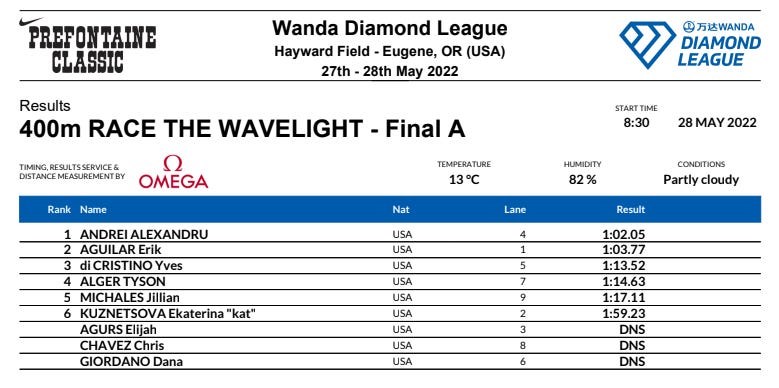

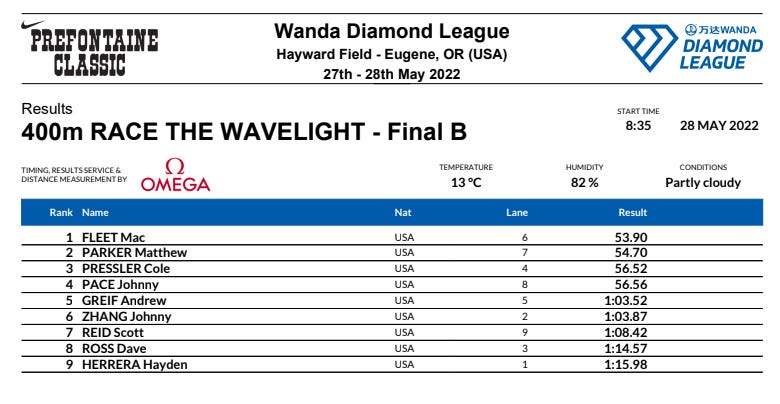

I did finish. In 1:14.63. Greif, in the same racing singlet he wore as an 18-year-old at North Bend, clocked a 1:03.52.

As Tracktown USA head of media operation Jeff Oliver noted, the results are “now a part of Diamond League history as they are online in the official results database.”

I’ve yet to see those biscuits, but I’m definitely going to frame my bib from my first Hayward memory. Plus, I have a time to beat for next year.

– Tyson Alger

Did so many people in your heat not run out of fear or respect?

Hell yeah, way to go!